London. With Summer comes the tentative hope in Europe’s art market capital, of a respite from the virus that has plagued the lives of its population for over a year. London is important to our journal because it is the locus for the tertiary art markets of Russia and the Middle East. With New York it also plays a significant role in the transaction of high-end Indian art. These two cities are also centres for international contemporary art, to which category some of the art that you will encounter in this journal belongs. The art procured and disseminated by Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Bonhams and Phillips is occasionally sourced directly from artists and even, in the case of Farhad Moshiri’s (b. 1963) painting, Eshgh (2007) – now in the collection of Dr Farhad Farjam – commissioned by an auction house. But this proximity of auction houses to artists exists only at the inception of a new market; in mature markets art is recycled via the tertiary market only after it has passed through several hands. If the countries in which this art is created operate restrictive or protective art markets, which is the case in Iran and in most of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) -with the exception of the Gulf- then local intermediaries are the only points of entry and exit. Here, the pecuniary intersection of the various local art world constituents is lubricated by hard currency transactions devolved to third States.

The Gulf is the art market centre of the MENA region. It has at its heart the emirates of Dubai, Sharjah, Abu Dhabi and Doha, which perform the role of filtering and presenting the art from the surrounding states and even India to an international audience. Local galleries such as Meem, Ayyam, and Third Line rub shoulders at regional fairs such as the recent in-real-life (IRL) iteration of Art Dubai, with specialist international dealers like Aicon, New York and San Gimignano’s Galleria Continua. National auction houses like Iran’s Tehran Auction and India’s Astra Guru hold, respectively, monopoly and leading positions within their national markets.

Dramatic external events have determined the nature of the markets throughout this region. The so-called Arab Spring, which began in 2010, has fractured Arab society. Two years before, the global credit crisis fissured the Gulf and had a particularly damaging impact on Dubai’s property market. Relations between the Gulf states are very changeable and the Abraham Accord between Israel, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain is particularly fragile. The cultural ambitions of Saudi Arabia’s 2030 Plan, will challenge the regional cultural predominance of the United Arab Emirates. One likely outcome will be a proliferation of schools of traditional calligraphy. Saudi’s Ministry of Culture declared 2020 to be the year of Arab Calligraphy and the Madinah-based Dar Al-Qalam Complex has revealed plans to become an international institute recognising competence in Arabic calligraphy. These cultural resurgences have been 80 years in the making. The Saudi Taibah (calligraphy) school was founded in 1942. The Arab initiated Hurufiyya movement and the Iranian Naqqashikhatt style of calligraphy appeared after the Second World War, and in Iran were conceived as a tonic to Gharbzadegi (Western struckness) a derogatory term coined by the academic Ahmed Fardid. Turkey has, as Andrea Sandri writes in the Journal, looked deep into its past in order to rekindle its former splendour. It has highlighted its deep reservoir of skilled crafts, perhaps at the expense of its regional art market leadership. But Turkey, and Istanbul in particular, still has a first-class art world and the advantage of a rich architectural history, which, as the re-consecration of the Hagia Sofia make apparent, is very relevant today. The great familial craft traditions of Iran, to which Nima Sarghachi alludes in his interview with the editor, enables a descendent of the original artisans of a sixteenth-century monument to restore it to its original state. India too is steeped in its past. Anindya Sen writes of Narendra Modi’s gift of Mahatma Ghandi’s hand-written interpretation of the Baghavad Gita to President Obama and of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) desire to promote the ancient culture of India.

So much of the evolution of the art markets in this region is dependent on the will of government. Yamini Mehta points to the importance not only of private patronage per se to the Indian art market, but to the collaboration between cultural benefactors like Kiran Nadar and the Indian government. The importance of these relationships was recently made apparent in the form of the Indian pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale; the fruits of a partnership between the Kiran Nadar Foundation and India’s Ministry of Culture. India should heed the plea of Kiran Nadar and facilitate more public/private partnerships.

‘ There are many forces propelling the art worlds of this region in multiple directions. There is the international magnetism of London, the Western-centric infrastructures of the Gulf States and the equally potent traditional and often inaccessible markets devoted to traditional practice locked behind the gates of political isolationism or the walls of cultural exclusivity. ‘

At present, according to Yamini Mehta, the Nadars and a handful of wealthy Indian families are almost single-handedly building the hardware of that nation’s art world. If their efforts can be harnessed to government, India’s febrile art market will thrive. The Gulf states, and more recently Saudi Arabia, have proved the most stable and supportive governments in recent years. The soundness of these ministries has led to the development of an unparalleled regional arts infrastructure, which will undoubtedly have a positive influence on the future value and price of Emirati art. Janet Rady refers in her article to the seminal role played by the Alserkal family in the development of the industrial area of Al Quoz in Dubai. The political stability that this highlights has enabled the passionate collector Farhad Farjam, as Roxane Zand discovers in her interview with him, to salvage and preserve precious relics.

There are many forces propelling the art worlds of this region in multiple directions. There is the international magnetism of London, the Western-centric infrastructures of the Gulf States and the equally potent traditional and often inaccessible markets devoted to traditional practice locked behind the gates of political isolationism or the walls of cultural exclusivity. Neither of these two states need to be permanent. In May I visited, for the first time in over a year, an exhibition at a private gallery in London. The October Gallery exhibition was devoted to the work of the Algerian artist Rachid Koraïchi (b.1947), titled, Tears that Taste of the Sea. The exhibition displayed seven of the pots that he had inscribed with talismanic symbols while beleaguered in Barcelona during the height of the Covid pandemic. The series of seven anthropomorphic four handled pots, entitled Lacrymatoires Bleues (2020) (fig. 1) and reminiscent of a person with arms akimbo were accompanied by a set of wall-based works titled Mouchoirs D’espair (2020).

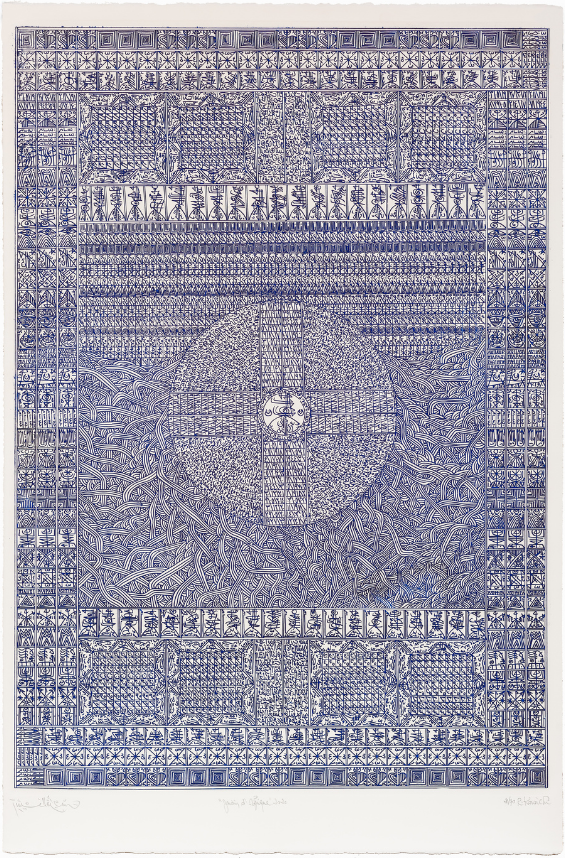

On the far wall, an etching of the artist’s seminal project, Le Jardin d’Afrique (2020) fig. 2 took the form of a Medina, with the addition of stylised waves. It was created in collaboration with the students of the National College of Art in Lahore at the time of the Second Lahore Biennale. The actual project to which this work of art alludes is a plot of land that the artist bought in 2018 in order to bury the dead and swollen bodies, washed up on the shores of Southern Tunisia of people from north and sub-Saharan Africa who had drowned. Koraïchi has funded, designed and created every monument in the enclosure, employing craftsmen to reproduce the designs of seventeenth century tiles. It is in every sense the Thiepval of North Africa.