‘ I just think we need a lot more private endeavour to become involved in the arts. While we will fulfil our part and responsibilities, it is impossible for such a large population to be sustained by one museum. ‘

YM:

In 2019 at the Venice Biennale, you announced Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye as the recipient of the commission for the permanent space in Delhi’s outskirts in Noida. The scope of the project was astounding and not like anything seen before in India. What qualities about his design attracted you the most? Could you give a bit of detail about the planned facilities?

KN:

Okay, first off I have to say that the location of the museum has been shifted out of Noida and is now going to be in Delhi, closer to the airport. It is going to be off the NH8 (editor’s note: national highway) and we have seven and a half acres of land. But … there is a height restriction for building there. David’s original design was vertical but now what we need is a horizontal space, so the concept has changed to that extent.

We worked with Malcolm Reading Consultants and appointed an eminent jury to assist us in the selection process. Glenn Lowry (editor’s note: Glenn Lowry is the David Rockefeller Director of The Museum of Modern Art, New York) and Chris Dercon (editor’s note: Chris Dercon was Director of Tate Modern, London 2011-2016, and, since 2019, president of the Association of French National Museums-Grand Palais, where he is overseeing the renovation of the Grand Palais) were on the jury, along with Malcolm who had envisioned the competition. I think there were approximately 60 architects who had applied for the commission. We narrowed it down first to 20, then 15, and then to the five who made the final presentation. David Adjaye’s selection was more or less unanimously agreed. There were two or three reasons. I think the most important was that he was very, very keen to do a project in India. Right at the start his enthusiasm for India came through. I mean, it was something he really wanted to do, and I thought that was a great attraction and of course, David, as a person, is very charismatic. And I think we got on very well. We really related to each other. The whole family seemed to sort of adopt him, Roshni, Shikhar, me, we were all very enthusiastic. And Glenn and Chris were persuaded and persuasive respectively, which made a lot of difference to our final decision. Even if there were any doubts, it didn’t matter because David was the right choice.

So, we have bought the land. David was here a month ago. He managed to make it out three days before the Covid Delhi lockdowns. He has presented his updated plan, which we have okayed in principle. We’re going ahead with it now. He has to get the drawings done (fig.3).

YM:

This is really exciting news. I think also having something by the airport where it is central and easy to get to but still a destination will be amazing. Is this already public knowledge?

KN:

It is public but we have not published our plans. You know, that part of town is definitely much more developed and has a real buzz. So, the only constraint we had was that we couldn’t build beyond twenty-three meters height. So that’s why it’s all sort of horizontal. But it lends a really different sense of joy to the project. And the feeling of space … so we’re building 900,000 square feet, out of which 400,000 square feet will be allocated for the car parks. But we might reduce the ambitious car parks the government wants us to build by about 200,000 square feet. But even then, it still gives me 700,000 out of which 500,000 square feet will be for the cultural centre / museum.

YM:

I am not only excited about the museum project, but envisioning how it could change the environment in the immediate vicinity. I was wondering, since you’re saying this, how much urban planning and infrastructure are part of making the museum a destination. Are you and Mr. Adjaye thinking along the lines of planned cultural hotspots like Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi or the Guggenheim, Bilbao, the latter of which has revitalised the city and the region?

KN:

Certainly, Bilbao is very central to my thoughts. You know, Delhi, when you really look at it post-Independence, there’s just one building – and that’s the Bahá’í temple – which has anything to offer in terms of modern architecture. (editor’s note: The Lotus Temple for Bahá’í worship was completed in 1986.)

YM:

So, in terms of making the KNMA a go-to destination, is there an aspect of it which is a bit like the Metropolitan Opera House or the Southbank Centre, where you pair it with theatre, restaurants, outdoor installations and hotels?

KN:

Yes, it is early days but we have two restaurants planned. One is going to be a café and one is going to be a sophisticated restaurant. We have an auditorium for 600-800 seats. We have studios for dance, for art, and music. We have art studios as well, of course. We plan to take a property right behind us in order to have residences for visitors. So, these are just some of the plans that we have in mind. And I told them, I want a home there too, close to the museum, so I don’t have to commute for two hours.

YM:

I think the thing, too, is that you realise that an institution like the one you are building is not in isolation. It is going to transform everything that is around it and make it into the destination.

We live in interesting times, and when the museums were open, they were a wonderful respite throughout the pandemic. Has the pandemic brought any changes or new ideas in museum design or forced you to think of the space and structure differently?

KN:

It has. One thing that has happened with the pandemic is the development of virtual museum spaces, which is here to stay. We have been investing heavily in our digital content. I think people will follow museums a lot more online as well but I think we would like to encourage the audience to come back and be with us physically as well as virtually. Hopefully sooner rather than later.

We are in a time when people are re-modelling their lives and thinking about what is important and meaningful.

YM:

I think people are probably looking at structures differently right now, too. Have you been to the Louvre Abu Dhabi? The airiness and open spaces for a hot climate and country…

KN:

I love the Louvre Abu Dhabi. I mean, that building is just divine! And what is wonderful is the finishing, the way they have built it. There’s nothing that’s not in place … the flooring, the way the walls are finished, it’s just stunning. India is hot too, but you are not going to feel stifled at our museum. It is going to be airy, with high ceilings, because we are not building many floors. But we are trying to minimize the number of floors and focus on the horizontal accent so that the sense of space is there.

We are using three different elements of white (for cooling) and one is for a porcelain jali (screen) to enhance airflow. We were telling David that we must prevent birds from landing on the porcelain jalis and so he has worked out an ingenious way to have discreet sound currents of animals of prey resounding from the porcelain, audible to the birds but not to us, to act as a natural repellent.

YM:

Your collection is eclectic and encyclopaedic, spanning ancient sculpture, court painting, pre-modern and modernist art as well as the art of today. Is the museum also going to have the same remit or is it going to be a bit more focused?

KN:

The museum is going to be equally eclectic. We’re going to have popular culture. We’re going to have miniature paintings, and antiquities. Of course, the emphasis will remain on the modern and contemporary because that’s the largest part of the collection. But these little niche collections will remain and we will have a small concentration of foreign artists who I have collected, such as William Kentridge, Olafur Eliasson, Ai Weiwei, and … Marina Abramović …you were there when I bought her work in Basel. So, these are the artists who will be there maybe, in a small gallery to show as international highlights. What I would love is a Van Gogh. I don’t have one.

YM:

I’m sure that that could be arranged. And of course, you have Raqib Shaw and a few other artists from the region who have crossed over into the international contemporary scene.

KN:

I have Anish Kapoor in the collection. I think of Anish Kapoor as Indian. I know he doesn’t, but his work is heavily influenced by his background. Raqib Shaw, Rina Banerjee, and Shahzia Sikander. I also have several works by Salman Toor as well.

YM:

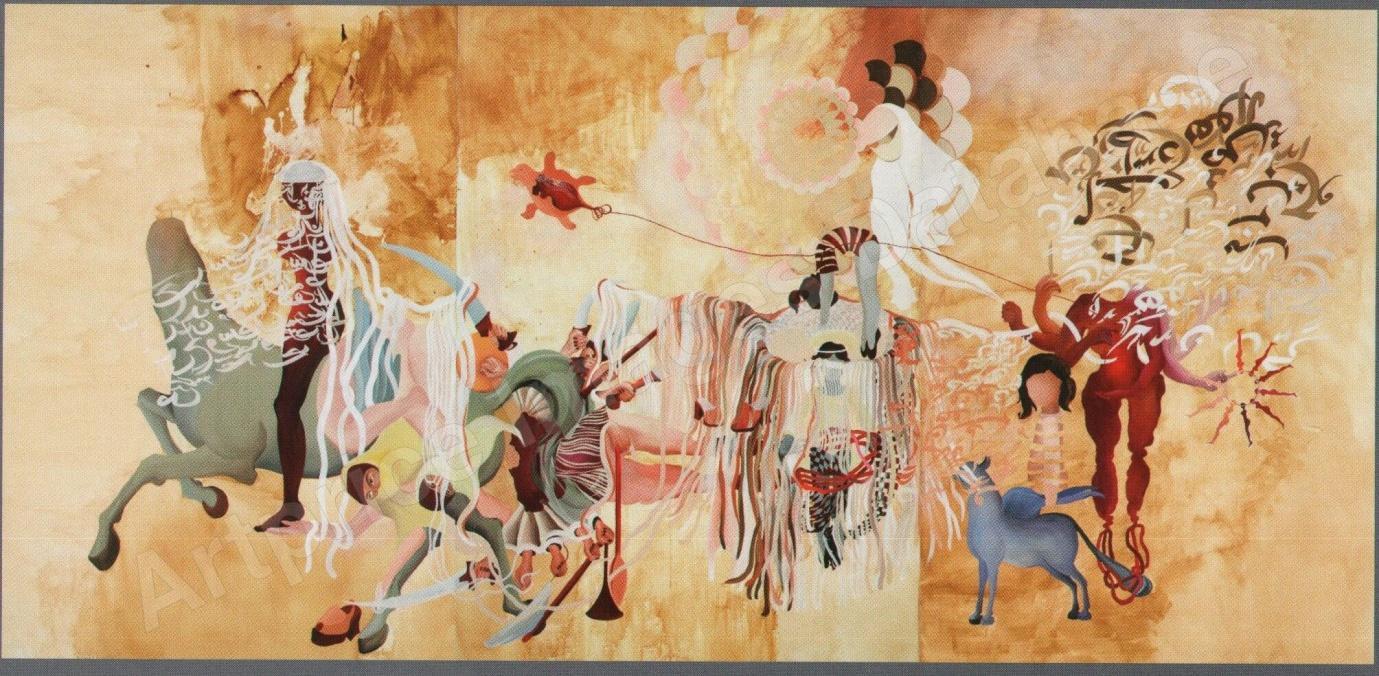

I definitely remember the bidding on your large Shahzia work, Veil n’ Trail (fig.4). It was for an early seven metre long work of hers that was consigned at the back of a Christie’s Day sale by Dakis Joannou for the modest estimate of $15-20,000. He probably did not think much of it. The contemporary department was dumbfounded when four people from the Indian team showed up on the telephones for that one lot to bid against each other and then leave with a flourish after it was sold to you for $325,000.

KN:

I remember sitting with my husband Shiv after that and telling him, ‘You know what I did. I just got this fabulous work but the estimate was $15,000 and I paid $300,000 for it ‘. He said, ‘Stop this idea of setting up a museum. You have no discipline!’.

YM:

Well, that was in 2008, and since then you have moved on to acquire so many more significant works at far higher prices, which reminds me of the adage about masterpieces, after a while it does not matter what you paid, just that you have it. Of course, it was different for Salman Toor, you bought his work early on and can show that as an example to your husband…. His current auction prices are booming. From estimates at $60-80-100,000 to $800,000 prices.

KN:

I have three Salman Toor works which I bought from Peter Nagy at Nature Morte two years ago. I got to choose the best works in the show. They were in the few thousands. Nowhere near the prices today but this was well before his Whitney show, which has really catapulted him. I wonder what is next for him (fig.5).

YM:

While your collection is world-renowned and well-documented for its twentieth century modernist focus, featuring works from the progressives. F.N. Souza, S.H. Raza, M.F. Husain, and Vasudeo Gaitonde, you are also the largest patron of South Asian contemporary art in terms of acquisitions and funding. I don’t know how many people realize that, but, for instance, I noted that the KNMA helped to produce Amar Kanwar’s acclaimed film, Such A Morning (fig.6), which was shown at Documenta 14. What other projects or commissions are you supporting these days?

KN:

I won’t say that there are a lot of commissions but we have worked quite extensively with Amar. We have also now co-funded his work, The Lightning Testimonies, for the Met with a few others. In specific terms of funding or doing work with any artist individually, we have not done too many commissions. So I won’t name anybody, but it is something we would like to get into and, as contemporary art grows in significance, there will be a lot of opportunities to do more.

YM:

The market for south Asian art rose so quickly between 2000 and 2008 and then, inevitably, it crashed. How are you finding the market these days for artists born specifically after 1960 or for art made after 2000? Are there more opportunities for the museum to collect contemporary art these days?

KN:

Yes, there are. Contemporary art has not rebounded to where it was in 2007-2008. Those prices, I don’t know when they will ever be realised again, but there is interest now in the younger contemporaries. And so, I think we will see something positive happening. Strangely, during the pandemic, the art market has sustained, if anything, or even gone up. Maybe not in this second phase of the pandemic, which we are having now, but through the first year and a half of the pandemic, auctions did very well. Art generally was upbeat. I think, with a lot of people, with new investors coming in at the lower level, with art they could afford, they now had time and everybody wanted to do things with their homes. You know, there were fewer expenses with no holidays, less travel so there was disposable income. A lot of the galleries are also putting across works of the younger artists with lower price points. Ashish Anand of DAG (Delhi Art Gallery) held a charity sale of 51 works a few days ago, and he sold every single one of them. They were comfortably priced but partly people bought because of charity and partly because there was value for money.

YM:

Do you have any particular criteria for acquiring up-and-coming artists into the museum programme? And are there any artists who are born post-1980 who you feel are coming of age now?

KN:

The second part of the question is a difficult question for me to answer. There are young artists who I am actively collecting and see great potential in, but, you know, once I start naming young artists, it becomes difficult and raises the potential for speculation. There are also a number of galleries that are doing exemplary work with contemporary artists and I’ll name one—Experimenter in Kolkata—they are doing fantastic work with their projects. They are serious gallerists. There are a number in Delhi also that are young gallerists displaying younger artists but I am not going to name anyone. If I mention names, it starts to become speculative and I don’t want to start that.

YM:

In terms of criteria for acquiring these up-and-coming artists, is there anything that you are really looking at specifically? Because obviously when you are buying, it is for posterity, not necessarily just to fill a space.

KN:

You know, I’m quite intuitive in my buying of young contemporary artists, I don’t necessarily go on very defined criteria. If something in the artist’s work attracts me, if it speaks to me, then I do my research and see what else the artist has done and then ask myself questions, weighing up why I should get into it or regard it just as a whim. So, I do that now, but even then, I do buy artists with quite a bit of intuitive instinct. I am open to the recommendations of some of the senior gallerists if they come to me saying that this is an artist of theirs that we should see and evaluate. And I think that is a good thing to do because you might miss out on some of the younger artists very easily. You don’t always get to see all the shows and there is only so much you can go and see and do. The concentration being on what you’re really doing with your major artists; that remains the focus.

‘ You know, I just think we need a lot more private endeavour to become involved in the arts. While we will fulfil our part and responsibilities, it is impossible for such a large population to be sustained by one museum. Even the national museums really need to be re-configured. They have received great donations such as the Amrita Sher-Gil paintings in the past and have fabulous works but I think private enterprise is really what is going to push the arts forward ‘

YM:

Museums can often find themselves with static collections, which serve as a snapshot of the time of the visionary collector or curator. How do you envision supporting contemporary art initiatives so that the collection can continue to grow and represent the current crop of artists even 50 years from now? Are you looking to build an acquisitions endowment of some sort?

KN:

We haven’t got the financial structure fully in place, but within a very short time, we know what we are going to have to do. I don’t know how many years I’m going to be here and then how the museum is going to function. It’s going to be there for posterity. So, we have to leave it in good hands financially so that it has a budget. But then we are also going to start looking to run it more professionally, with governance, boards for management and collections, and while I have control, I can institute these things, and this is something that I have to do. The other thing we really have to do, which is absolutely beyond necessary, is we need to expand our team. We are working with a skeleton team. It is a brilliant team and I must say Roobina Karode (Director and Chief Curator of KNMA) has been a tremendous asset to us, along with the other curators and the people we have, but the museum is going to need a structure which might be a little different. This is a very important aspect that we are studying very carefully; how to expand the team and which way to go.

YM:

Despite India’s population, its impact on global institutions is not as significant as you might expect for such a large global population. What do you think can and will change that in the future?

KN:

You know, I just think we need a lot more private endeavour to become involved in the arts. While we will fulfil our part and responsibilities, it is impossible for such a large population to be sustained by one museum. Even the national museums really need to be re-configured. They have received great donations such as the Amrita Sher-Gil paintings in the past and have fabulous works but I think private enterprise is really what is going to push the arts forward (fig.7).

YM:

I think at least from the international perspective, what we are starting to see is people who might not be building their own museums, but are joining the boards of major international museums.

KN:

Yes, there is more participation and the chance for influence grows. But also, honestly, I would think that some of these international museums, whether Chicago or MoMA, or others, should look closely at some of our KNMA shows. The Zarina show (editor’s note: Zarina Hashmi (1937-2020)) that we have just concluded was such a spectacular event that somebody could have travelled it lock, stock and barrel. And why not? These are areas that are under-represented now more than ever and it would be great to develop more reciprocity between our institution and others. I sent Glenn [Lowry] the updated plans of the museum and got him to speak to David [Adjaye]. And I must say he was wonderful. He spoke. He gave his input, what he felt. But I am going to talk to him about doing more on Indian art. I think somebody has to start pushing this envelope (fig.8)

YM:

The Zarina show is just one example amongst many of how the KNMA is redefining and expanding the canon for South Asian art. So many artists from her generation struggled and achieved recognition late in their lives. It is great to see that you are not just ‘pushing the envelope’ but firing on all cylinders because there is the exciting building project with a world-renowned architect, there is the actively growing art collection and then there is securing all of this for posterity. This undertaking is a tremendous responsibility that you are offering to the public good and it is hugely appreciated and valued by everybody in the arts community. It is a great start for India and will hopefully be a beacon to many for years to come.

Kiran Nadar

Chairperson, Kiran Nadar Museum of Art

Trustee, Shiv Nadar Foundation

Kiran Nadar is Founder and Chairperson of the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art. Mrs. Nadar is a Trustee of the Shiv Nadar Foundation, which, among its transformational educational initiatives has established the SSN College of Engineering in Chenna, (today among the top private engineering colleges in India), Shiv Nadar University, VidyaGyan schools, and Shiv Nadar School, in addition to the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art. Mrs. Nadar is a member of the Rasaja Foundation, an educational, scientific and cultural institution (founded in 1984 by the late renowned artist, art historian and art critic Jaya Appasamy) where she promotes educational initiatives for girls from impoverished and under-served communities.She is a member of the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA) She began her career in advertising, communications and brand development. Aside from her philanthropic work in art and education, she is a champion bridge player as a member of the ‘Formidables’ team,with which she has represented India, winning numerous competitions nationally and internationally.

Kiran Nadar lives in Delhi, India, with her husband Shiv Nadar, Founder, HCL and Chairman of the Shiv Nadar Foundation.